The Blizzard of 1978 was possibly the worst winter storm of the century, impacting the whole city of Cleveland as well as the entire Eastern United States.1 As assistant financial editor of the Press John Sabol recalled, “A lot of us at the Press, I mean, we didn’t go home at night. We stayed at the Holiday Inn at Lakeside.”2 Sabol recounted the worst of the three storms that happened that January, lumped together into one major weather event indicative of the capricious Northeast Ohio weather. With accumulation of up to two feet of snow, the entire city spiraled into a standstill. People stayed home from work, schools closed down, and cars and traffic stalled to a grinding halt. Some Clevelanders even resorted to putting cardboard boxes on their heads to attempt to protect themselves from the arctic blasts, which clocked in at eighty miles per hour.3 Reports and commentary on the blizzard point to two significant criticisms of urban populism, that being Kucinich’s youth and narrow scope in constituents.

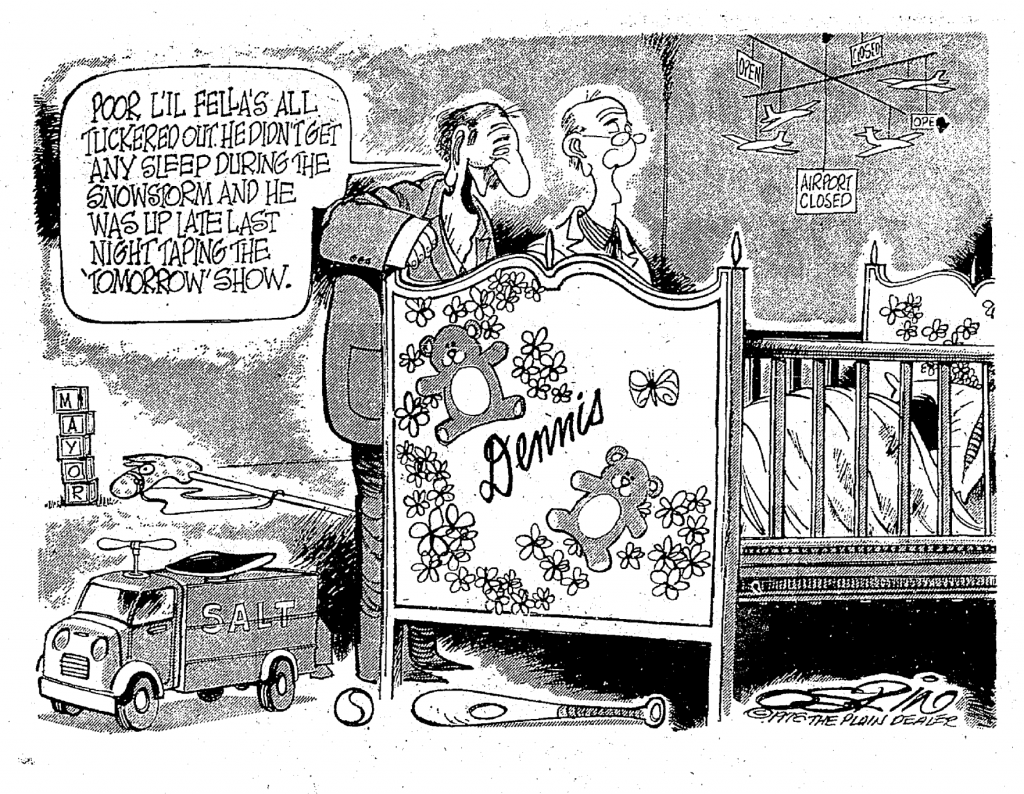

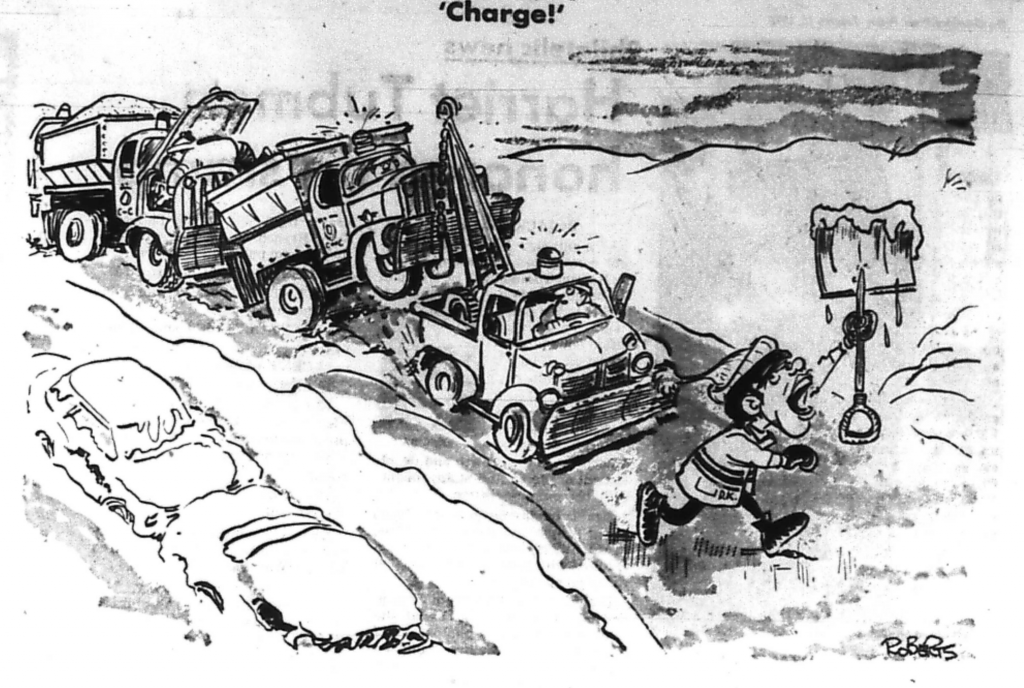

Despite Kucinich’s opponent in 1977 being a year younger than him, Kucinich was regularly described as young to the point of being juvenile.4 This was mainly due to his irascible temper and teenage appearance, leading to his colloquial nickname, “the boy mayor.”5 Through political cartoons, the Cleveland Press and The Plain Dealer both characterized Kucinich’s role in the blizzard as inexperienced. Ray Osrin, Archie comic artist turned political cartoonist, depicted Kucinich in a crib labeled “Dennis,” stating that he was sleeping after a long day of taping the Tomorrow Show.6 In a similar vein to Ray Osrin’s cartoon in The Plain Dealer, longtime political cartoonist for the Press Bill Roberts created a cartoon that also mocked Kucinich’s youth. The cartoon portrays Kucinich as a boy playing in the snow, holding up traffic.7

Both Osrin and Roberts were able to use the problems of government inefficiency to emphasize Kucinich’s appearance and boisterous behavior, attacking the style-over-substance notions of urban populism. Roberts’ cartoon is more overt, equating Kucinich’s brash, juvenile political attitudes as a crutch for response to the Blizzard. Osrin’s cartoon highlights not only Kucinich’s youthful outlook and appearance but also his relentless search to uphold his public image. During the Blizzard, Brent Larkin wrote about Kucinich’s control of the media to sway thinking on the storm from the Cleveland populace.8 This appears in the Call and Post, Cleveland’s African American newspaper, which saw Kucinich’s response to the storm in a more positive light.9 Osrin makes this issue an integral part of the cartoon, as Kucinich is sleeping due to being exhausted from filming an interview for the Tomorrow Show. This cartoon communicates the press’s reaction to Kucinich’s waning grasp on the media in general.

This perceived inefficiency of Kucinich’s government lent itself to criticisms of urban populism, specifically through the perspectives of the papers that reported on the storm. The Cleveland Press under Louis Seltzer slanted its views to cater to a broader audience within the city.10 As a result, some of the paper’s sections gave news from the neighborhoods of the Greater Cleveland area, including a dedicated suburbs page. In the early 1970s, the Cleveland Press created the Community Weekly, an “ad wrapper” section that focused on local news to accommodate the large number of advertisements on Wednesdays.11 An article on the storm in the Community Weekly addresses the concerns of councilmen regarding Cleveland’s roads being blocked.12 The Plain Dealer’s assessment of similar complaints six days prior takes a different approach, one more focused on businesses affected by inefficacy and steeped in investigative journalism. It noted that, although Kucinich’s aids argued that the mayor was assuaging the buildup of snow, he was actually sleeping.13

While these articles take different approaches, both point towards growing resentment of Kucinich’s weak political platform and inaction towards the Blizzard by highlighting different demographics. During the Blizzard, the Community Weekly took on the perspective of the suburbs under Cleveland’s municipal government, blaming Kucinich’s administration for the lack of plows on the road.14 The Plain Dealer’s focus on business also lends itself to taking on Kucinich, whose economic rhetoric relies on fighting corporate interests sucking economic autonomy out of the city. The Plain Dealer and the Cleveland Press implicitly assert the idea that Kucinich’s urban politics are too narrow through their own critical perspectives. The approach to Kucinich from the news changed once he was elected mayor. Originally, Kucinich used the press to bolster urban populism. Late, the press framed their stories to work against Kucinich’s political strategies. This relationship between the mayor and the media would falter and only worsen once the petition to recall Dennis Kucinich gained momentum.

- “1978 Ohio Statewide Blizzard,” Ohio History Central.

- John Sabol, interview with the author, April 3rd, 2022.

- “Blizzard was century’s worst,” The Plain Dealer, January 27th, 1978.

- Brent Larkin and Fred McGunagle, “Candidates wind up their race for mayor,” Cleveland Press, November 7th, 1977.

- McClelland, 67-68.

- Ray Osrin. Political Cartoon in The Plain Dealer, January 12th, 1978.

- Bill Roberts, “Charge!” The Cleveland Press, January 13th, 1978.

- Brent Larkin, “Dennis is tops in using media,” The Cleveland Press, January 28th, 1978.

- “’Baby, It’s Cold Outside,’” Call and Post, January 14th, 1978.

- “Cleveland Press.” The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. From Case Western Reserve University. Accessed March 16th, 2022.

- John Sabol interview.

- Darlene Johnson, “City councilmen storm over snowplowing,” The Cleveland Press: Community Weekly, January 18th, 1978.

- Joseph L. Wagner and Donald L. Bean. “Snow removal spawns a new storm.” The Plain Dealer, January 12th, 1978.

- “City councilmen storm over snowplowing.”