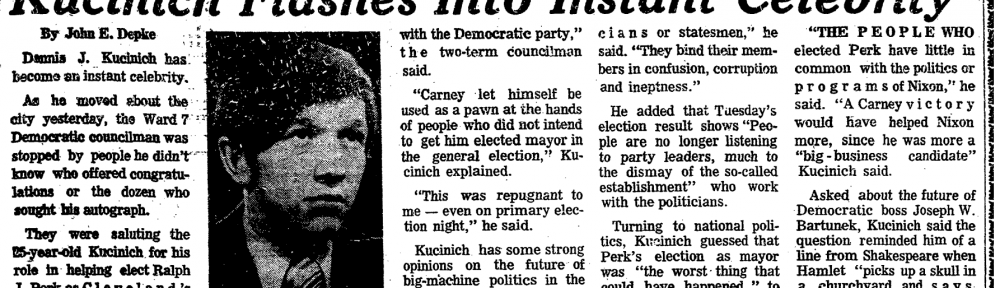

Dennis Kucinich’s rise to celebrity through the press in Cleveland was indicative of the moment in America that he was raised in. Born in the West Side, Kucinich became an underdog candidate fighting against what he saw as special interests, including big business and corrupt politicians.1 This rhetoric reflected the disdain that many Americans felt towards party politics as Kucinich aimed to fall outside of party lines. Kucinich was then elected to city council in 1969, juggling the beginnings of his political career with his education at Case Western Reserve University and his marriage.2 Articles written in Cleveland at this time highlight the relationship created between shoe-leather journalism and politicians, Kucinich being was no exception. Kucinich’s ascension to the forefront of Cleveland politics functioned on a commitment to news media.

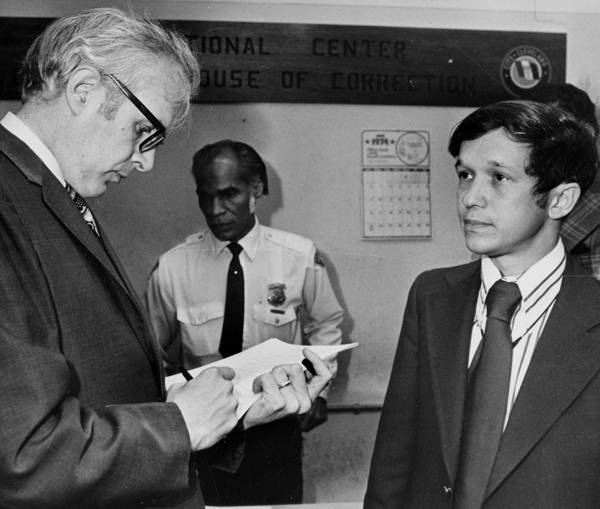

On city council, Dennis Kucinich played the role as a political outsider, expressing disdain for the functions of municipal government. Although Kucinich originally campaigned and supported Republican mayor Ralph Perk, Kucinich would later turn on him, criticizing Perk’s role in the greater political issues plaguing Cleveland. Multiple articles in The Plain Dealer describe a political war led by Kucinich to criticize the mismanagement of Perk’s government. These accusations made by Kucinich were in regard to the Warrensville Workhouse, a dilapidated facility used to house working inmates.3 Kucinich led a council probe to investigate the maintenance issues of the Workhouse. During the investigation, Kucinich accused Perk of relaxing enforcement while also allowing the workhouse to deteriorate. Other liberal councilmen like George Forbes did point out the financial follies of Perk’s administration, but Kucinich appeared more vocal in his attacks.4 The reason for this rested firmly on Kucinich’s forte: the press in Cleveland.

The Plain Dealer’s reporting on Kucinich’s probe into the Warrensville Workhouse reveals that Kucinich’s politics were dependent on the media. Urban populism as an ideology firmly rests on the idea that special interests are too intertwined with government, creating inefficiency. To get this point across to Clevelanders, Kucinich needed the publicity for it. An issue like the Warrensville Workhouse’s dismal state might have been routine city council procedure, but for Kucinich it was a media opportunity. One of the articles regarding the workhouse explicitly mentions the fact that Kucinich required news reporters to see an inspection of the old Cleveland workhouse, much to the dismay of the rest of city council.5 Though the findings left much to be desired, the investigation regardless helped to destabilize Ralph Perk’s mayoralty.6 Kucinich saw that any problem in the city could be turned into a moment for publicity, regardless of its importance or relevance. The media could then act as a conduit for his public outcry and community organizing, both of which are staples of urban populism.

Just months into his time on city council in 1970, the Sunday Plain Dealer Magazine published an article detailing the political and personal life of Dennis Kucinich. The article is positive towards Kucinich, portraying him as an up-and-coming firebrand politician cutting through red tape to local stardom.7 The minutiae of his life made him personable and relatable to the populace of Cleveland. Five years after, the Sunday Plain Dealer Magazine published an article on the ways politicians are able to control the media. The article is a half-humored attempt to provide information on using the media as a politician, acting as if the audience will run for office. Using second person, its advice relies on conveying an understanding of the mutual relationships between politicians and the news. Featured political figures include Kucinich and his later GOP rival George Voinovich, who impart their wisdom to the audience and reflect their coy ways of using the media for political advantage.8

These articles convey how Kucinich and the media formed a symbiotic relationship during his tenure on city council. The article from 1970 is a comprehensive account of Kucinich’s life at that point and reflects the positive outlook that papers like The Plain Dealer took. Overall, what seems like an honest account of an up-and-coming politician is more so a public relations move. Aiding this notion, the 1975 article on the media specifically puts the ideas of authorities and politicians in conversation with each other. Kucinich is then seen as a contemporary of the press, concurring with its editors and reporters. This portrayal of Kucinich coincides with Larkin’s sentiments of Kucinich as an ally to the press at this time.9 Pictures supplement this positive outlook, showing Kucinich canvassing door to door in harsh weather conditions. Although this article pokes fun at the way politicians use the media for their own gain, Andrzejewski paints Kucinich as clever rather than manipulative. For The Plain Dealer especially, Kucinich’s political strategies were favorable.

This honeymoon for Kucinich and the press would not last into his mayoralty. By the next year, Kucinich’s image faltered he came to terms with a fierce, midwestern foe: the capricious Northeast Ohio weather.

- The idea of what “special interests” entails is discussed in Kucinich’s interview with Tom Snyder on the Tomorrow Show after the recall election and can be accessed on YouTube.

- Arthur Allan, “The youngest councilman’s rat race,” Sunday Plain Dealer Magazine, May 3rd, 1970.

- “Cleveland Workhouse,” The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, from Case Western Reserve University, accessed April 16th, 2022.

- Joseph L. Wagner, “City Council picks up the ball,” The Plain Dealer, August 26th, 1974.

- Thomas J. Brazaitis, “Workhouse tour findings unimpressive,” The Plain Dealer, June 12th, 1974.

- “City Council picks up the ball.”

- “The youngest councilman’s rat race.”

- Tom Andrzejewski, “Run for office! Manipulate the media!” Sunday Plain Dealer Magazine, July 27th, 1975.

- Larkin Interview.